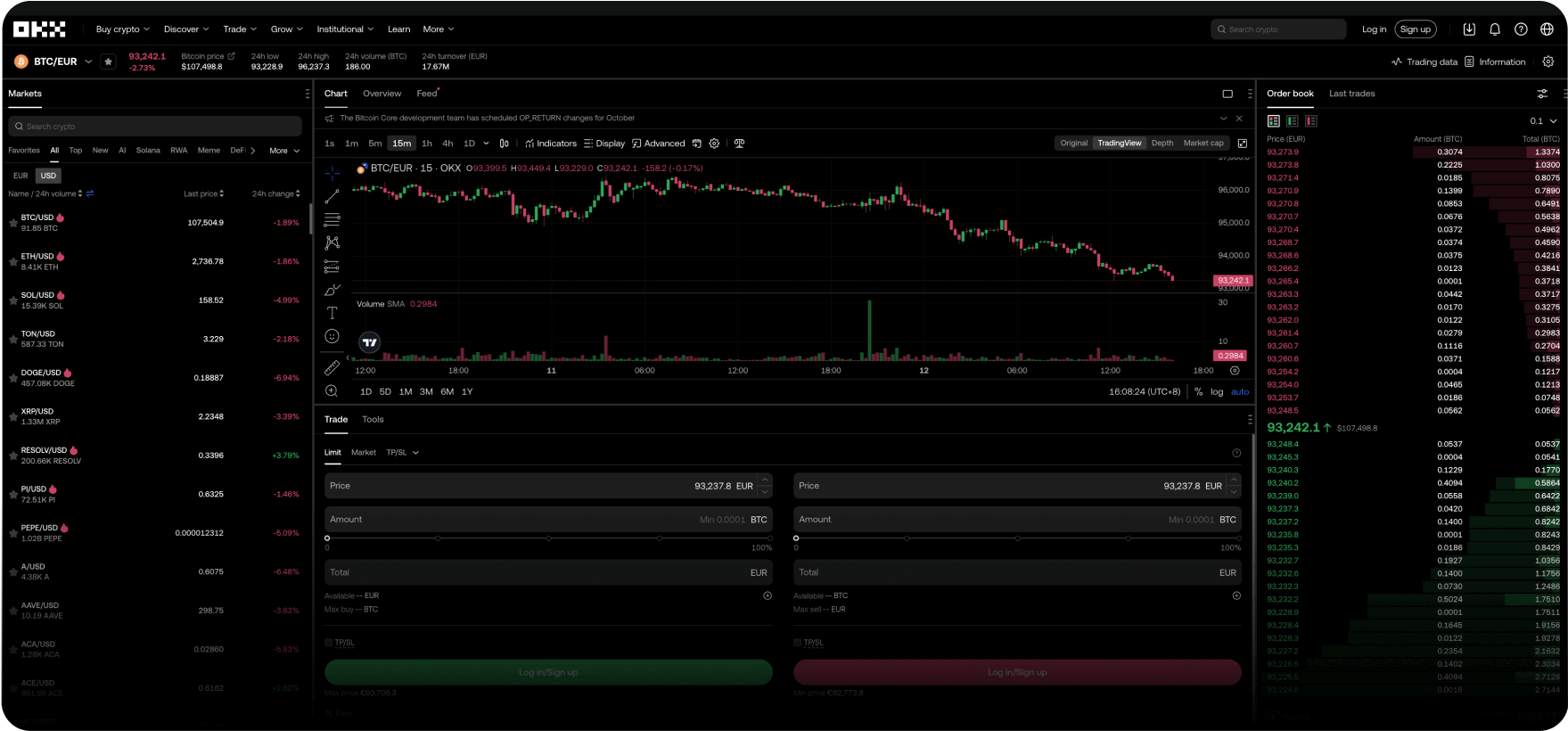

Digitaalisten dollarien maailmanlaajuinen tilisi

Hyödynnä alhaisimmat maksut, nopeat transaktiot, tehokkaat API:t ja paljon muuta.

Mukanasi joka vaiheessa matkan varrella

Me opastamme sinua prosessin aikana aina ensimmäisestä kryptokaupastasi kokeneeksi treidaajaksi kehittymiseen asti. Mikään kysymys ei ole liian vähäpätöinen. Ei unettomia öitä. Tutustu kryptoihin luottavaisin mielin.

Valmentaja Pep Guardiola

Selittää ”hullun jalkapallomuodostelman”

Kirjoita järjestelmä uudelleen

Tervetuloa käyttämään Web3:a

Lumilautailija Scotty James

Tuo mukanaan koko perheensä

Onko sinulla kysymyksiä? Me voimme vastata niihin.

Mitä tuotteita OKX tarjoaa?

Kuinka voin ostaa bitcoinia ja muita kryptovaluuttoja OKX:ssä?

Missä OKX:n toimipaikka sijaitsee?

Voivatko Euroopan unionin asukkaat käyttää OKX:ää?