Crypto Infrastructure Myths: Why "Build and They'll Come" Not Work?

Original Author: Saneel Sreeni

Original compilation: Deep Tide TechFlow

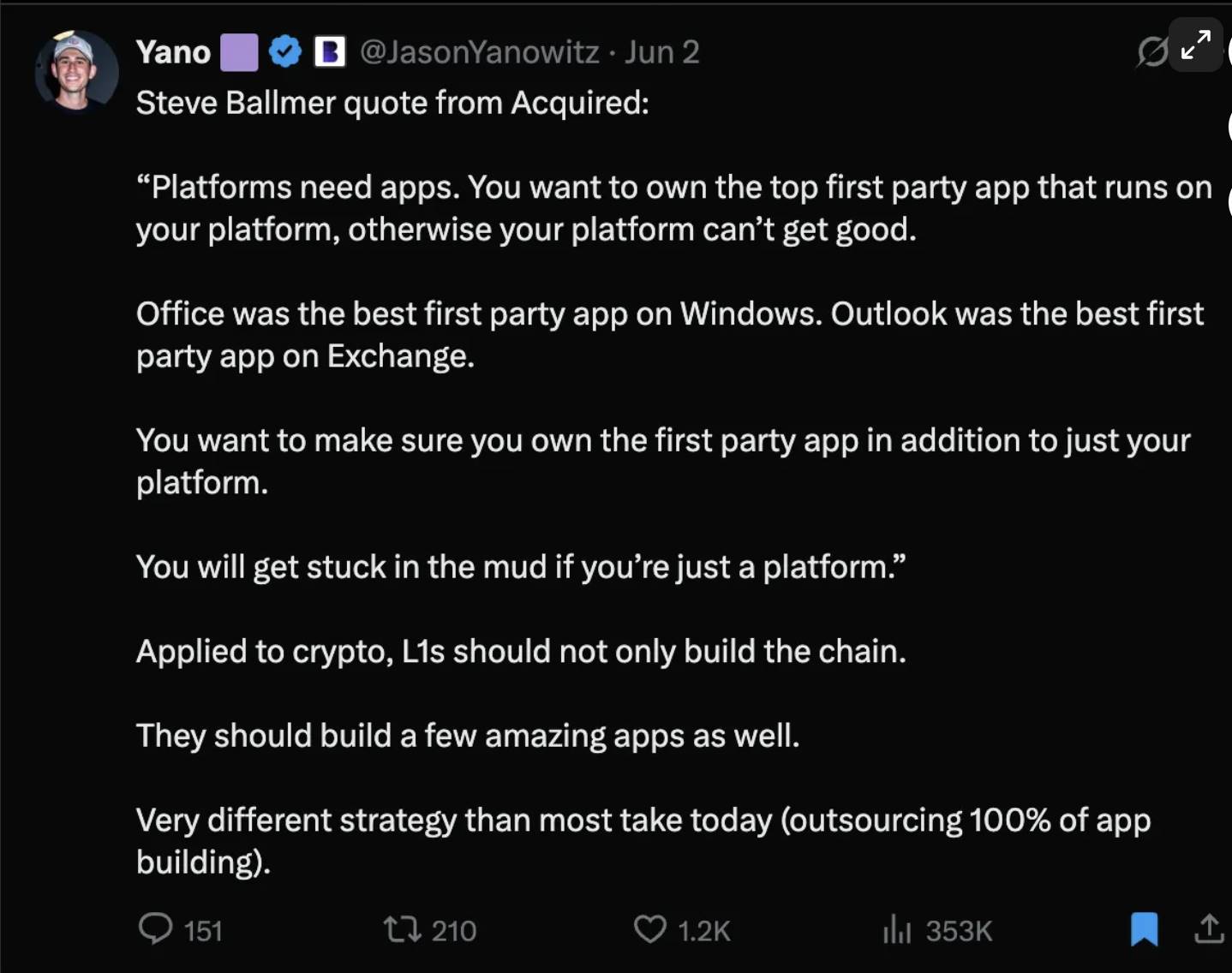

The following is a tweet from Jason Yanowitz:

may be partly inspired by two things:

(1) many of the recently launched Layer-1 blockchains are underperforming, and

(2) Outstanding success of Hyperliquid and HyperEVMFor

readers who are not familiar with the crypto space, Hyperliquid is a decentralized perpetual contract and spot trading platform that has quickly dominated the market, even surpassing some centralized exchanges. They launched their own high-speed EVM blockchain based on the success of the trading platform. At the time of writing, Hyperliquid has a market capitalization of approximately $11 billion and a fully diluted valuation (FDV) of $33 billion.

Hyperliquid is one of the first cases to successfully lead the development of a new Layer-1 blockchain through its primary revenue stream app. I generally agree with Jason. However, most new Layer-1 blockchains don't start out with the same advantages as Hyperliquid; Its founder, Jeff, previously ran one of the best high-frequency trading firms in the crypto space and has ample reserves of funds to avoid the need to rely on external funding.

As a result, I've come up with some ideas about strategy and go-to-market (GTM) for new Layer-1 blockchains and alternative ideas for building applications on top of them, especially when taking more traditional paths such as venture capital funding and building entirely new infrastructure (if your Layer-1 blockchain doesn't have significant functional differentiation and is simply mimicking other projects, these suggestions may not work for you).

My views are largely based on my on-the-ground experience at Ritual, as well as close observation of the strategy and execution of other Layer-1 blockchains with strong ecosystems. I'm still learning, so I may revise my views in the future.

In summary, here are some of my takes:

Proactive bootstrapping vs. "

Build and they'll come" was a strategic mindset that was prevalent in the crypto space prior to 2021, when the infrastructure was far from adequate. At the heart of this philosophy is that if you build a new chain or Layer-2 (L2), developers will come spontaneously and try to attract new users and capture value through your chain's tokens. This strategy worked for a time, because technologically sound chains with investment value were scarce at the time, and the infrastructure sector enjoyed a long-term premium. However, over time, this premium fades away, especially as a large number of new chains lack practical use and appeal for applications (most of which are just imitations or forks).

Obviously, this strategy doesn't work anymore, at least for new blockchain projects. One of the few ecosystems that has recently successfully executed this strategy is HyperEVM, but even then, its success is not entirely due to this strategy. The success of HyperEVM relies heavily on Hyperliquid Core (exchange) as a core application, creating real value for $HYPE holders and the Hype ecosystem (and enriching many active users prior to the Token Generation Event (TGE)).

In contrast, we're now seeing a large number of Layer-1 (L1) and Layer-2 (L2) projects adopt this line of thinking from the start, believing that they can make up for the shortcomings by handing out grants and pure branding, but ultimately fail.

That being said, it's hard to build "anything". It's hard to build infrastructure, and it's hard to develop applications. Especially in the crypto space, building isn't just about deploying code – there's a lot of work to be done, including go-to-market (GTM), operations, legal compliance, and more, which are often underestimated.

When you're building a Layer-1 blockchain (provided you're building an entirely new architecture rather than a simple fork project), it's both a huge technical challenge and a huge go-to-market (GTM) task. No one can be completely sure what a "killer app" will be, so it's your job to build the product and work with developers to support the birth of high-quality apps as much as possible to maximize the likelihood of success for your Layer-1 and the developers who trust you.

This means several options for infrastructure teams:

-

Assemble a stronger team and do everything in-house, including developing top-level applications:

This approach may work, but it has the following problems:

-

(a) Good talent is hard to find.

-

(b) Internal recruitment of the best talent means that more money needs to be raised from investors, which investors are not buying today. (I know Hyperliquid did it all with 10 people, but most founders don't have the strengths and resources to get started like Jeff.) Even so, their performance was insane.

-

Not only do you need to hire engineers, but you also need to hire people who specialize in GTM, operations, marketing, and legal. While there may be opportunities for cross-platform collaboration at scale, this will take a long time to materialize, especially since each app can vary dramatically.

-

Follow the old path of "build it and someone will come" + give out a lot of development grants:

This strategy is usually used by some "grant hunters" with mediocre teams and lack of application differentiation, and it does not work well in the long run.

-

Actively leading the ecosystem:

I mean taking a more proactive approach by building prototypes or some lightweight applications on top of your infrastructure and working with other developers/partners to drive those applications into full use.

Developers want to see that you're not just talking, but actually putting your time and effort into it. At the end of the day, no one understands the potential of this infrastructure better than the people who developed it. In this way, you can:

(a) showcase new and engaging applications;

(b) demonstrate the likelihood that it is achievable on your infrastructure;

(c) Have some influence in the direction of ecological development, and not just through the distribution of funds.

Now, approach (3) still requires great talent to build applications in-house, but it's more of a proactive practice designed to help build a real-world protocol from the ground up without requiring significant resource investment or impacting improvements to the core infrastructure. Functionally, it's almost like providing platform support or incubation for these companies.

Could this approach be a more difficult, slower path? Yes. But I think it's a more long-term approach for projects that are still refining their core infrastructure/are in the early stages. It's this approach that we've taken at Ritual, building apps that we want to see on Ritual with projects like Ritual Shrine that we think can be killer apps in crypto and AI.

But it's not just us – Solana had a lot of active building activity in the early days when working with FTX, Jump, and a few other teams. Several new projects that are popular on crypto Twitter (CT), such as Plasma, MegaETH, Monad, and others, have taken a proactive approach to creating a core set of protocols native to their ecosystem on top of existing protocols.

I expect this to become a dominant strategy (and increase the difficulty of really standing out on top of the technical work).

In some cases, I wish we could fully prototype many Ritual Shrines in-house and operate them ourselves. But I also recognize that these projects require dedicated teams to succeed in product and GTM execution (which may be a better fit for the market than we are, even if we have what I consider to be one of the strongest cross-functional teams in the field).

If we can build side-by-side with these teams while providing strong financial rewards to external developers, that's still a win. This allows us to "own" it in a figurative sense, while introducing new perspectives and new talents.

In short, in short: yes, it's great if you can have top-of-the-line first-party apps on your new infrastructure. But if resources are limited, then try to actively guide your ecosystem in the form of prototypes, building with them, rather than lazily approaching the process.